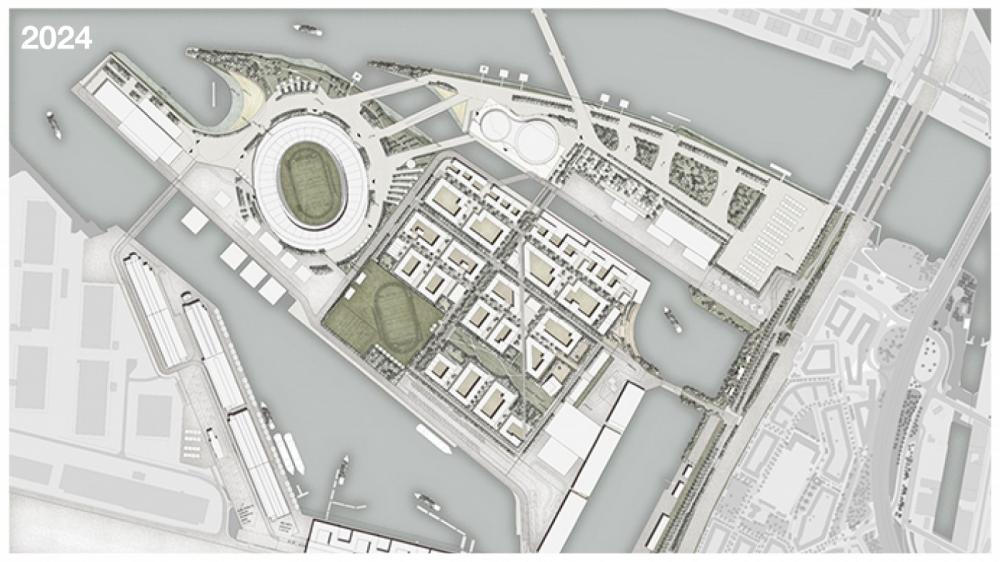

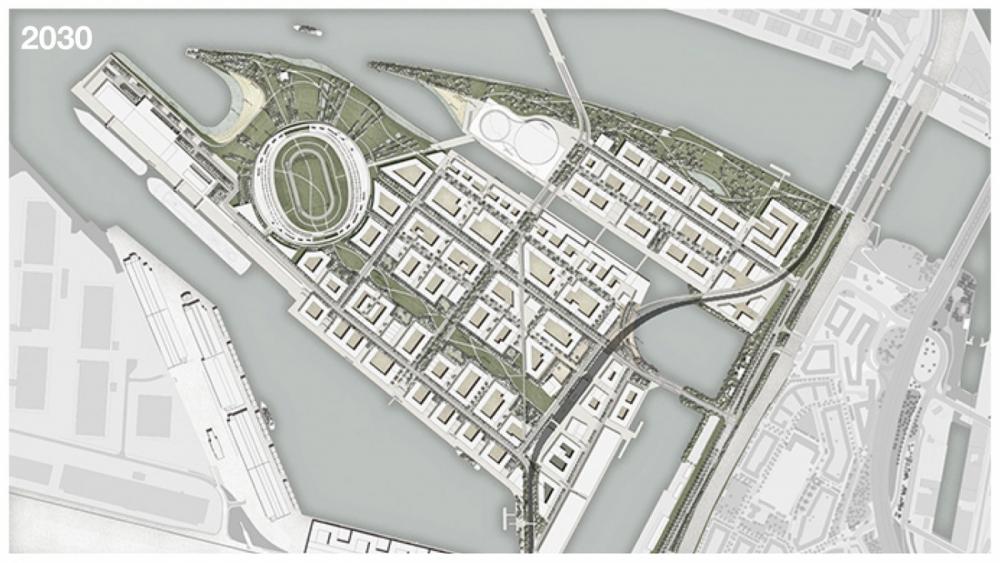

Hamburg is generally seen as the “greenest city” in Germany. This reputation is based on the famous plan by Schumacher and Linne in Hamburg and Oelsner and Tutenberg in neighboring Altona of the early 1920s, with the former as chief planning officers and the latter responsible for the parks and gardens. Their strategy was to create a city-wide network by combining elements of the urban landscape— the merchants’ and shipowners’ gardens dating back to the sixteenth century and the newly emerging modern building complexes. Since then, this plan has been regularly added to and refined, thereby retaining its validity to this day. Many elements of this network were created in connection with major events in society: starting in the mid-nineteenth century, more or less at the same time as the World Fairs, the tradition of horticultural exhibitions developed into a technical, aesthetic, and social display of the capabilities of horticulture. While the iconographic structures built for these fairs, such as the Crystal Palace in London (1851), the Eiffel Tower in Paris (1889), and the Atomium in Brussels (1958), also shaped the image of the particular city in the wake of the exhibition and became tourist attractions, the parks created for the horticultural exhibitions were generally maintained as public amenities for the citizens. In contrast to Berlin, which hosted three world fairs, the metropolitan region of Hamburg/ Altona has so far underscored its reputation as a “green city” with seven horticultural exhibitions. Fischerspark, Donnerspark, Wallanlagen, Planten un Blomen, and Wilhelmsburger Inselpark are just a few of the public parks created between 1869 and 2013 as a result of these exhibitions. Knowledge of this “green tradition” is deeply anchored in the collective memory of the city—just like the port, the river, and the use of clinker brick as a building material. Against this backdrop, in conjunction with the 2024 or 2028 Olympic Games, modern sports infrastructures and a further park were to be created—in addition to a new residential and commercial quarter—as items of lasting value for the city. The plan was to create a park that would have made a “leap across the Elbe” possible and was to have completed the “feather fan” plan of “urban greening” toward the south, connecting Lohsepark and Wilhelmsburger Inselpark.

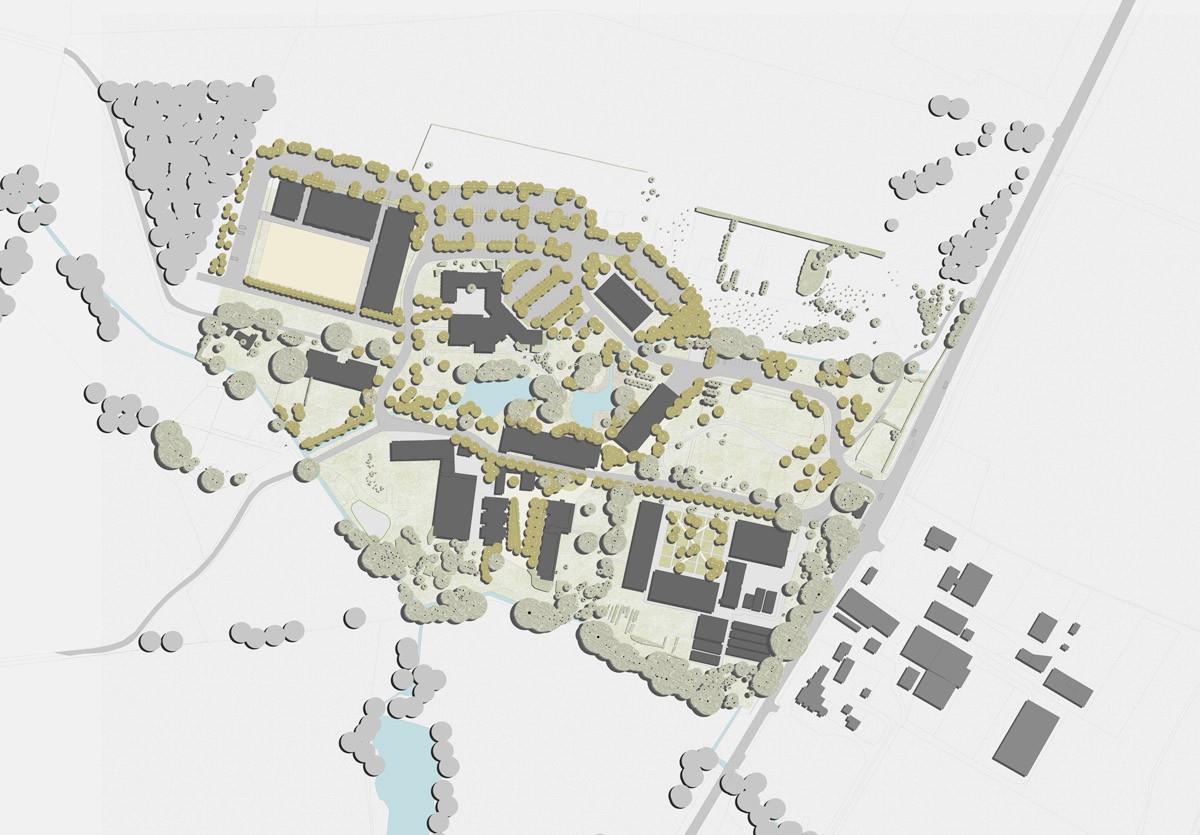

The new park, which is much smaller than most of Hamburg’s major parks, owing to the amount of space available to it, picks up on a central feature of the historical models, with strategically positioned visual axes connecting to the water expanses of the Elbe and the Outer Alster. As you leave the densely built quarter, the view through the park opens up toward the Elbe Valley and expands the scale of the elongated area of open space on the river bank beyond its borders. The passing ships are also part of this setting. Although the fruit and refrigeration center was gradually shifted westward, cargo vessels still ply the Elbe: a reminder of international trade routes and far-distant ports.

When the Hamburg electorate voted against the bid for the Summer Olympics in a referendum on November 29, 2015, the project was suspended.

© dpa/Kcap, Arup, VOGT