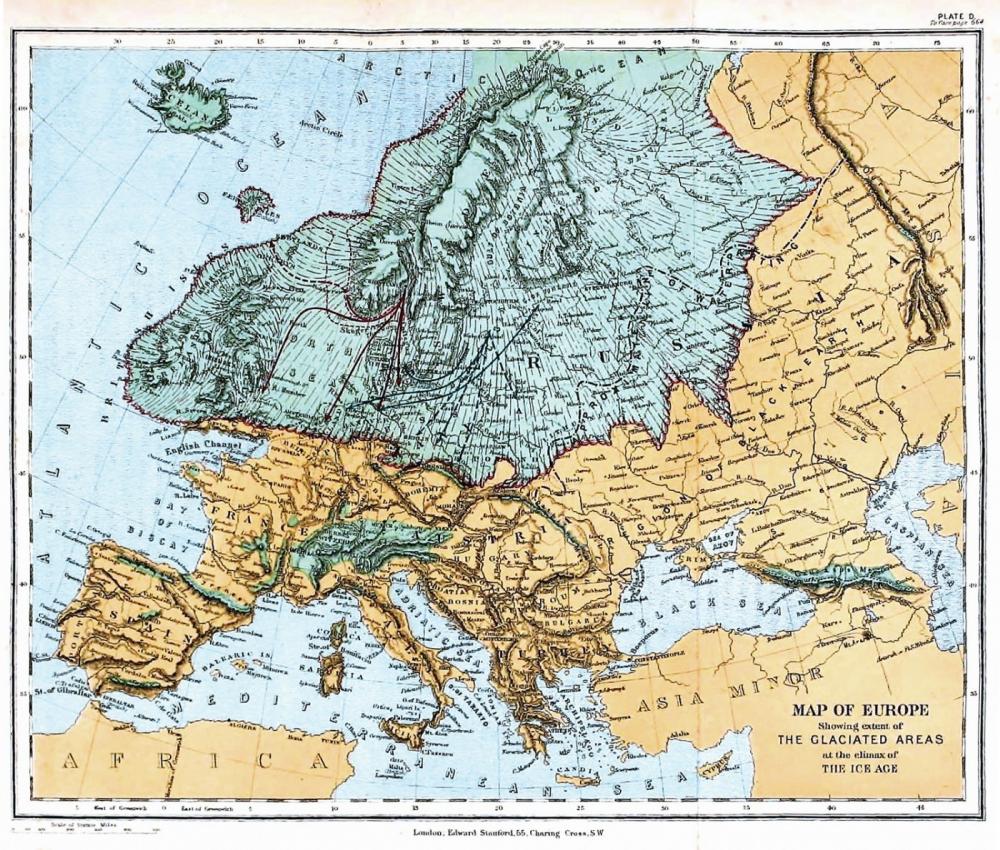

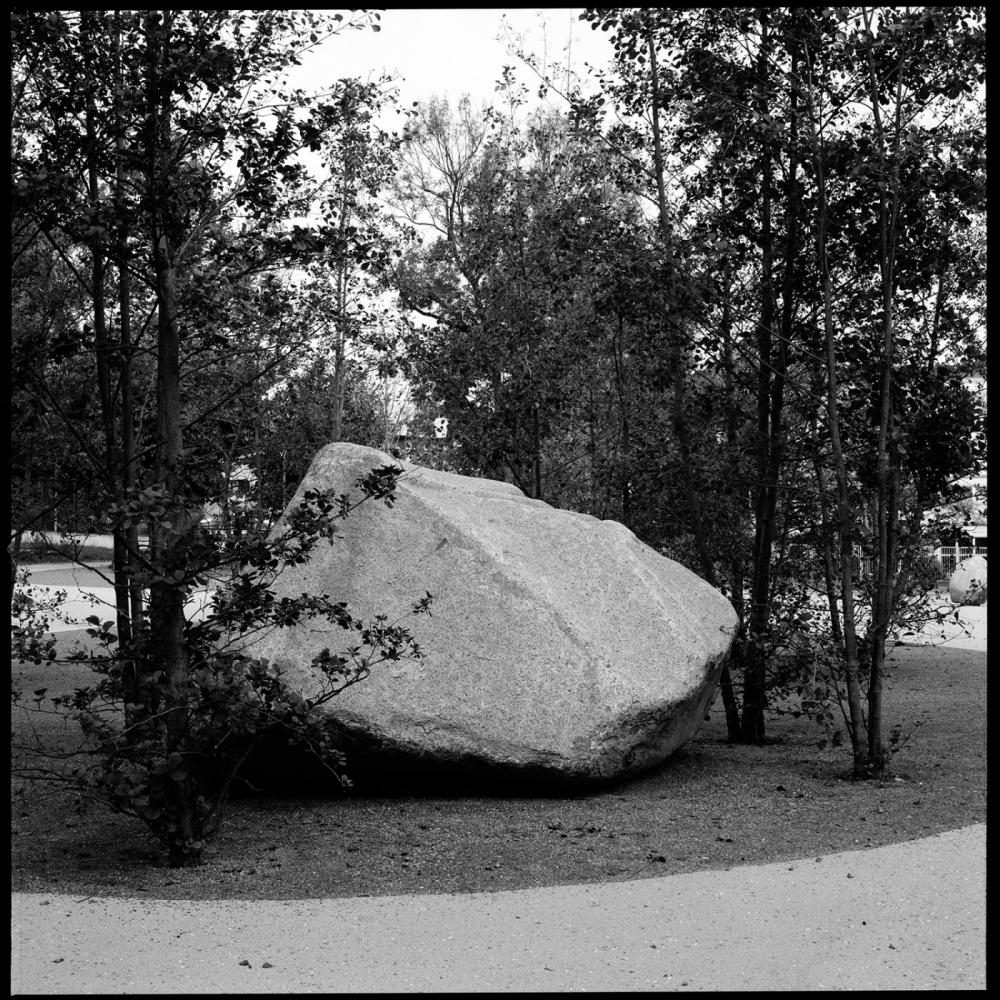

They are called Düvelstein or Devil’s Stone, Mövenstein or Möves’ Stone, Alter Schwede or Old Swede or Buskam: glacial erratic boulders whose names mostly date from a time when the geological inconsistency with the site of the find could not yet be scientifically explained and was, therefore, ascribed to the devil or mystical giants, who were supposed to have hurled these gigantic boulders to their current location—particularly aimed at objectionable churches, which they seem to have missed though. And although the extent of the glaciers has been scientifically proven since the nineteenth century and the origin of each boulder can now be accurately established by mineralogical analyses, the sight of these erratics is still amazing.

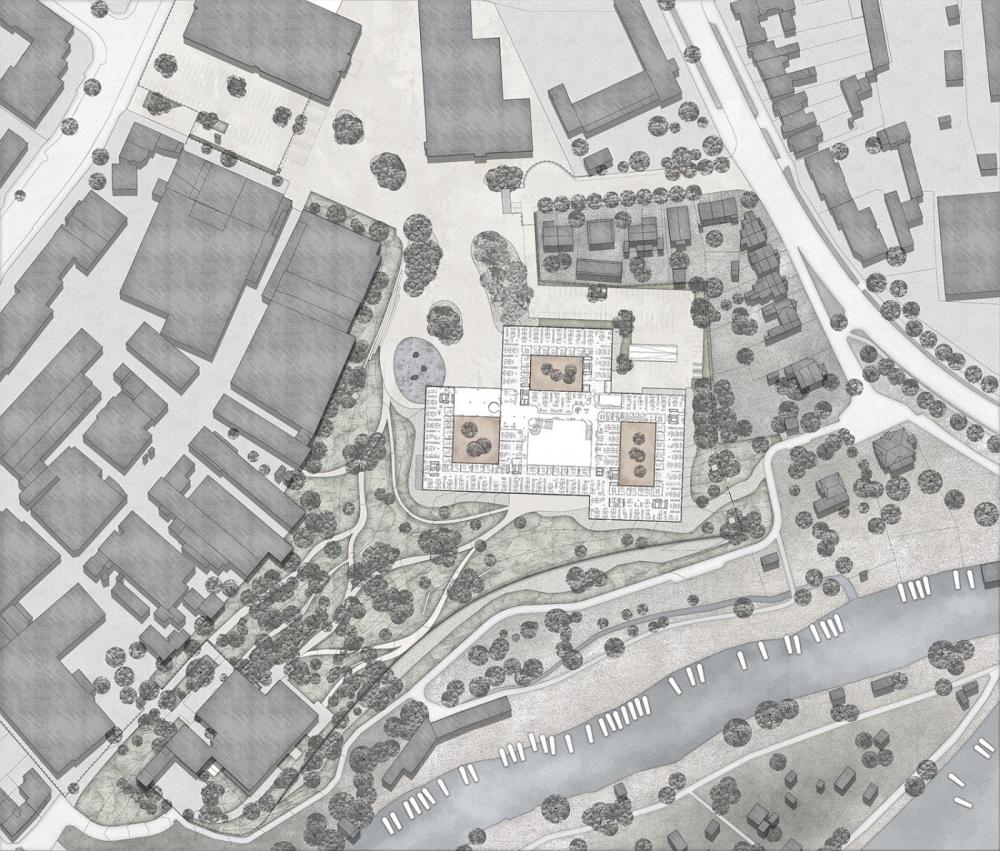

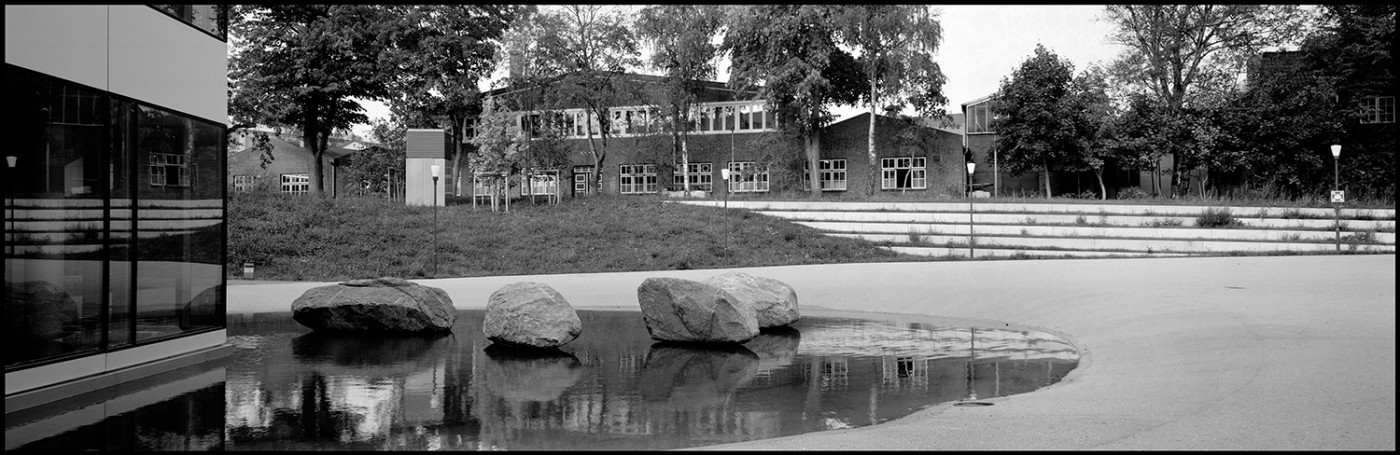

The migration of these erratic boulders, the transport of such huge rocks of up to several thousand tons over literally hundreds of kilometers, is not a local phenomenon but can be found all over the world wherever landscapes were formed by glaciers—whether deposited visibly on the ground or localizable by earth sonar in deep soil layers. The design of the ensemble of research, development and administration buildings of the company links the campus to these glacial relicts and their migration: giant monoliths ostensibly floating on water, standing upright, or resting in a grove create unexpected images and vistas. Like many other erratics found in North German landscapes, these specimens originally come from Sweden. Transported over thousands of years on or in the flowing ice of a glacier mass to be finally deposited at their current location, a field owned by the Dräger family near Lübeck and a gravel quarry on the Danish island of Fyn, they made the last part of their journey in a mere few days on an SLT or heavy-duty tractor unit.

The courtyards also contain references to the local geology: not in the form of a landscape shaped by glacial processes, but as brick surfacing made of fired clay. The bricks are laid unevenly with a few millimeters’ variation in height creating a surface relief, accentuated by precipitation and retaining rainwater. The familiar material from the local building tradition is juxtaposed against something foreign: the distinct growth patterns of North American swamp or bald cypresses (Taxodium distichum), Chilean monkey puzzle trees or pines (Araucaria araucana) and Japanese weeping larches (Larix kaempferi pendula), which we mostly know from the front gardens of suburban neighborhoods, turn these small groups of trees into autonomous objects placed in courtyards only open to the sky. Like the erratic boulders they, too, are travelers brought from faraway countries to the Hanseatic city.