The task of transforming the shipyard complex, formerly inaccessible to the public, raised questions about the typology and dimensions of the open spaces that form the matrix within which the new district was to be developed. The lack of any local patterns and the very size of the site require it to be considered at the level of the urban landscape: the yardsticks for the master plan were not small neighborhood parks but rather the sea, the straits, and the woodland at one of the most prominent locations within the city.

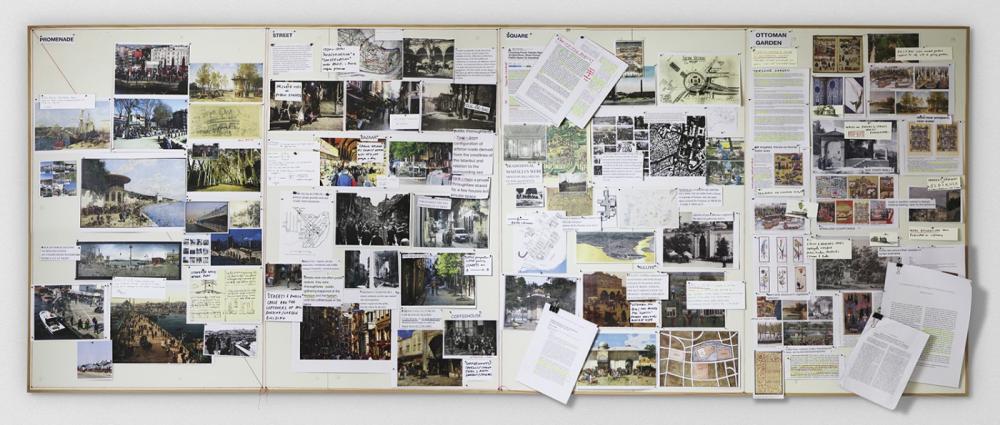

Istanbul—like Rome—is almost unique among Europe’s metropolises in that the infrastructures that once supplied the city are still in evidence in the surrounding territory. Deposits and fragments relating to more than two thousand years of history document the city’s utilization of existing resources and the basic requirements it relied on to support the livelihood and prosperity of a potent urban culture.

Waterways

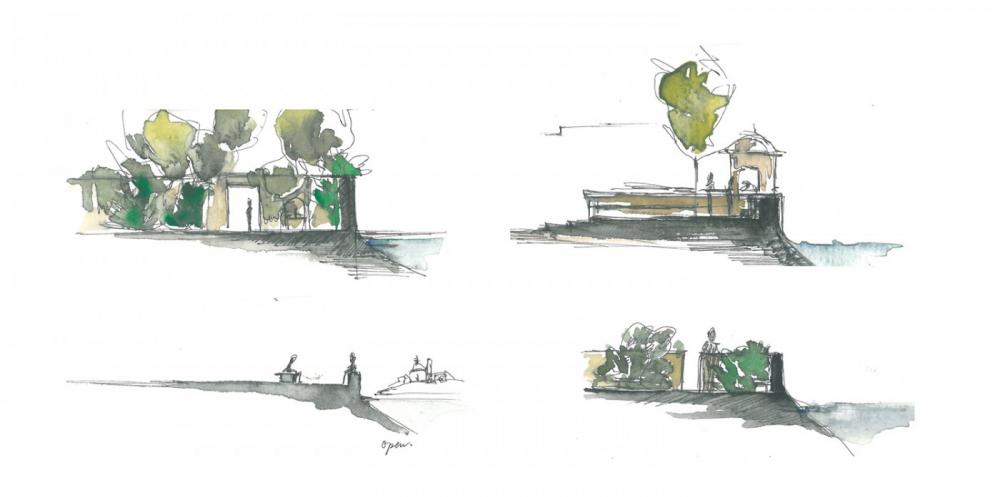

The forests to the north of Istanbul are of vital importance for the city. They were once used for hunting and to provide wood to build ships and heat the city’s numerous thermal baths, while the resulting clearances also freed up land for cultivation. Fresh water for drinking and bathing was collected in reservoirs. It was transported over long distances, sometimes aboveground and sometimes out of sight underground, flowing through caverns and along aqueducts and canals. Once inside the city, the water was then piped back to the surface, often inside very small architectural structures: the kiosks, which were originally designed by rich patrons as places for the poor to collect water, not only symbolize the economic, social, and religious significance of water but also point to the underlying geology and the system of waterways. These are far more than simple elements of the secular infrastructure, appearing to the outside observer today like metaphors in an English landscape park.

The Street and the Forest

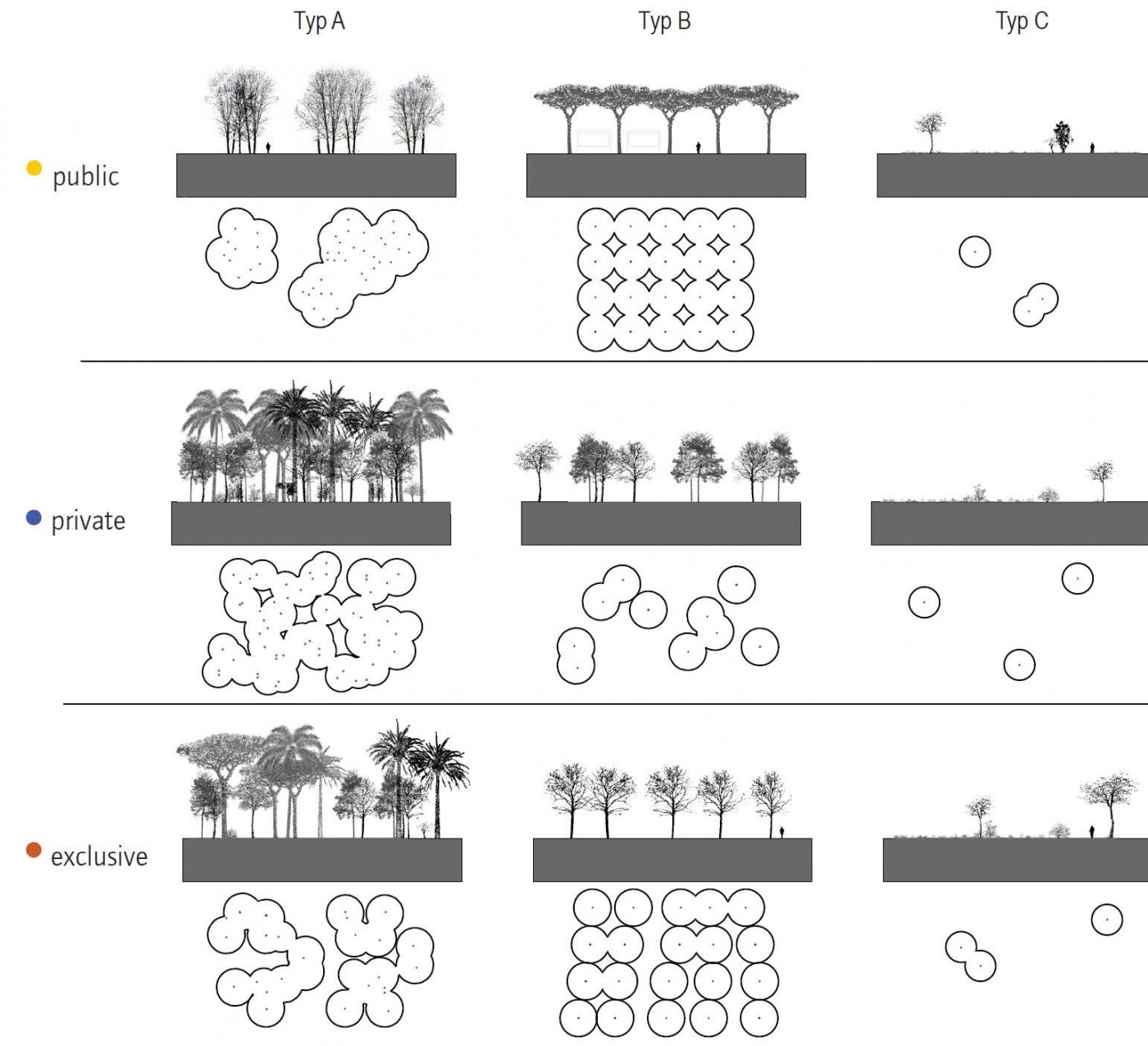

In addition to the inaccessible gardens and parks belonging to wealthy citizens, which are still largely closed to the general public, the streets and courtyards in Istanbul have traditionally been regarded as public places, much like the city’s mosques, cemeteries, and markets, which are often protected by walls and roofs. Given the size of the metropolis, however, there is an overall lack of open space today—a situation that was given widespread exposure in the vast protest movement against the destruction of Gezi Park, Istanbul’s first public park.

This has led to people’s appropriation of the extensive forest landscapes to the north of the city, which have long been used informally for recreational purposes. New infrastructures are being created and becoming established on a routine basis, though this increase of the city’s leisure amenities has not resulted in the area’s becoming more accessible to the general public—rather, the primary outcome has been a partial privatization of the space. At the same time, the forests are steadily being enclosed by the expanding city and its new, large-scale infrastructures. This not only poses a threat to the local flora and fauna but also undermines the important function the woodland serves, helping to cool the city and supply it with fresh air.

Openings in the City

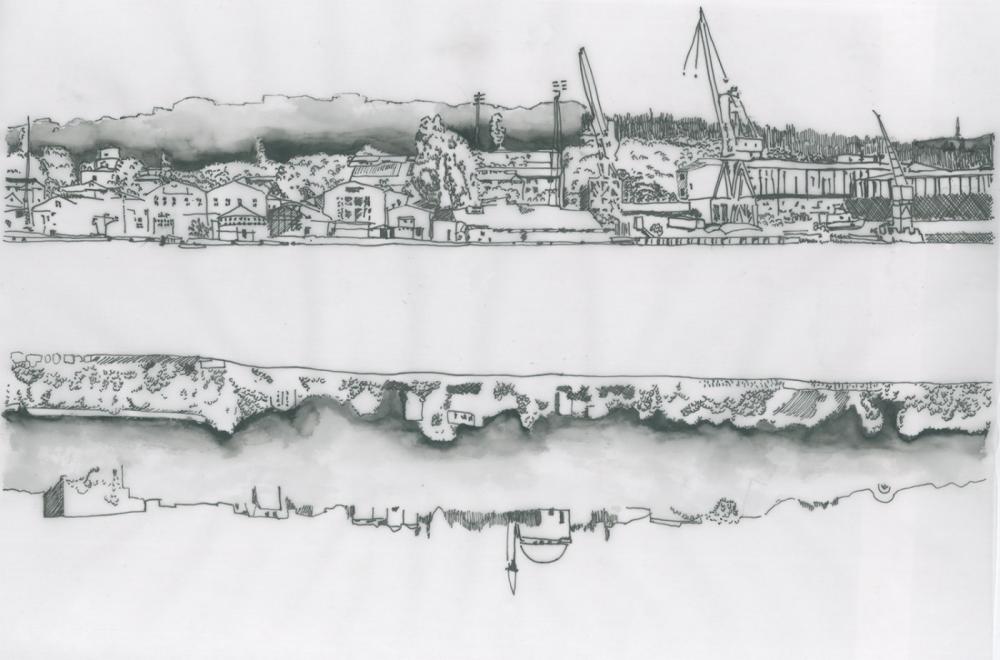

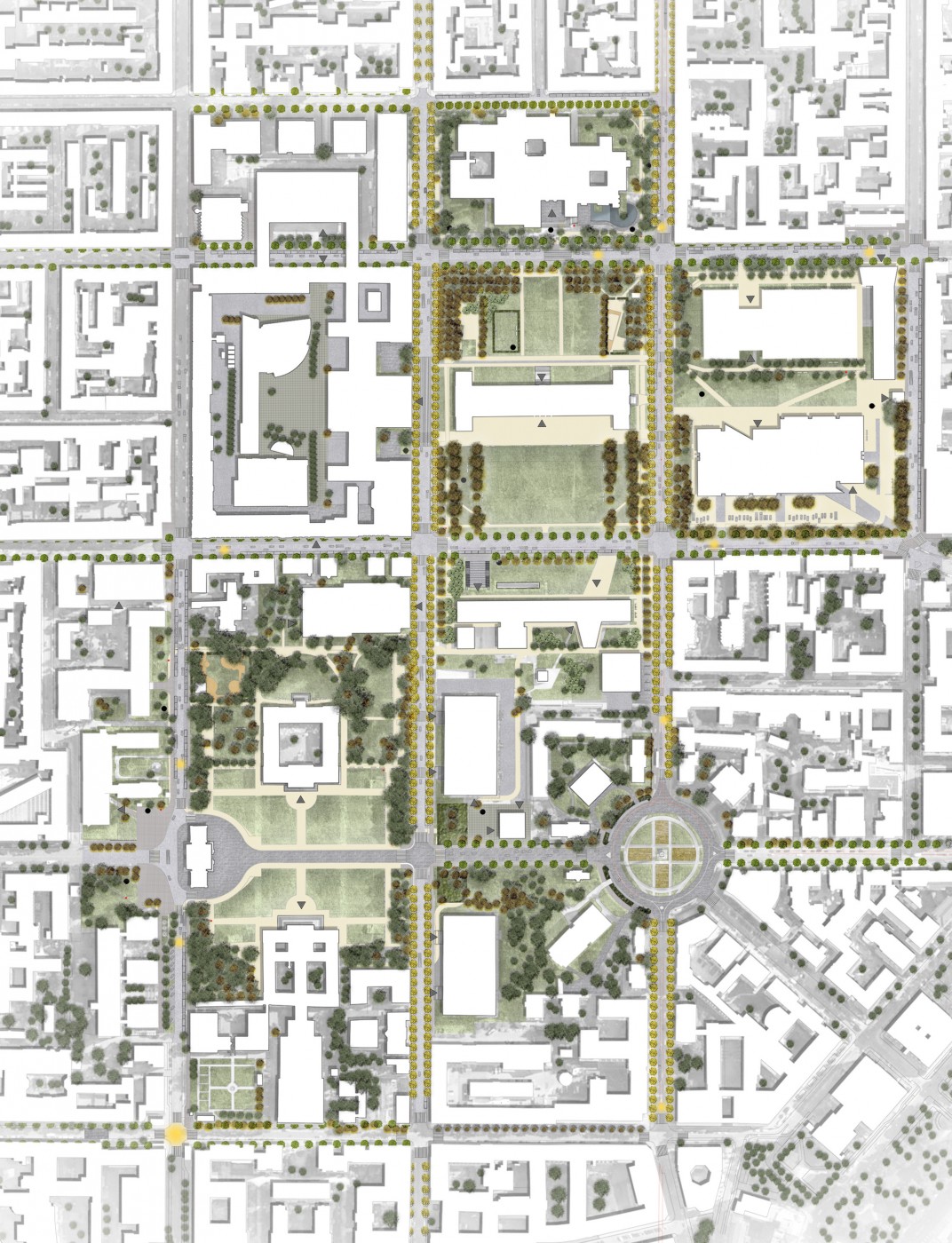

While the forests are ultimately being transformed into privatized structures, the timely planning and development of formerly inaccessible areas within the city have created the potential for open spaces with long-term stability. The Haliç shipyards, founded in 1455 by order of Fatih Sultan Mehmet on the site of the former Genoese colony, were among the world’s shipyards longest in service. The site is located on the Golden Horn, directly opposite the old center of what was once Constantinople. And although the area is bordered to the north by densely built neighborhoods and a small park, the waterfront was so far inaccessible.

Looking in—Looking Out

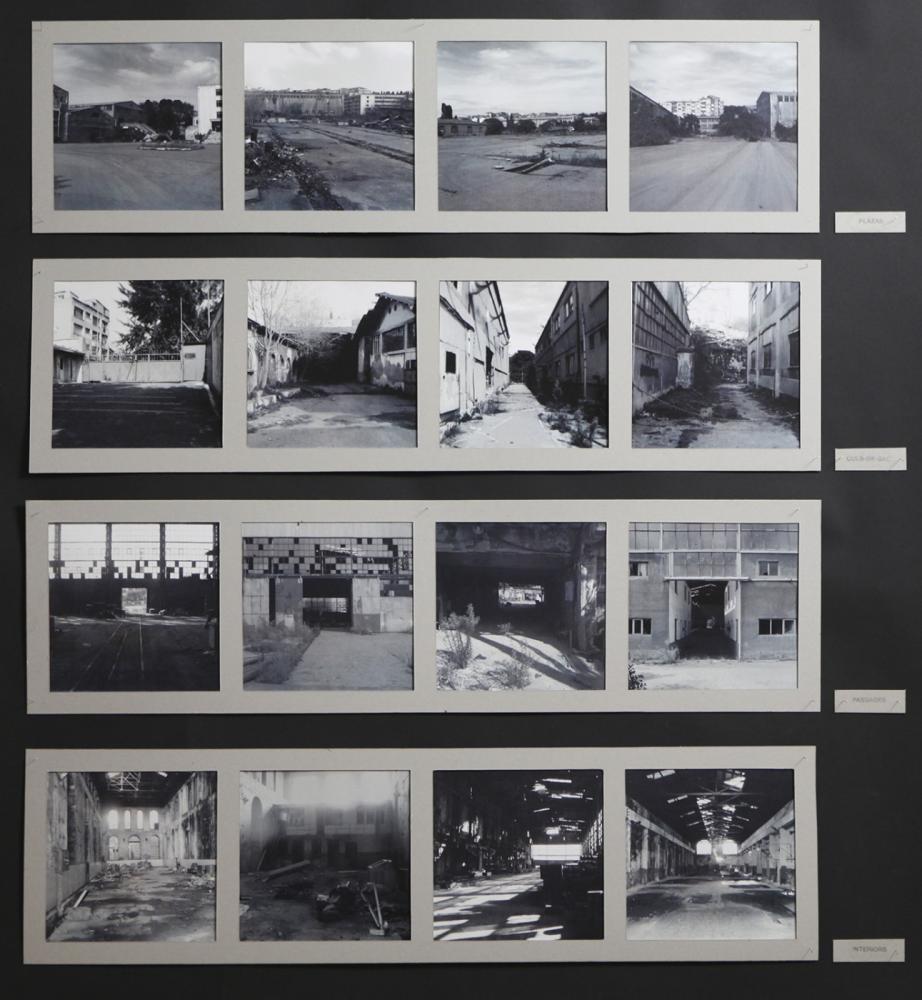

The first step in appropriating the disused area was a photographic study of the site. While the maps and aerial images tend to show the large structures and the embedment of the site into the city at the macro level, the subtle nuances in the spatial structure and the peculiarities of the local topography are revealed at the closer range of a pedestrian. The documented walk provided some initial ideas about suitable open-space typologies and how they might function in the new quarter. A long waterfront promenade forms its backbone, supplemented by a multitude of squares, lanes, passages, and gardens. Much of the typology follows local traditions: fountains and kiosks offer free drinking water, while walls create thresholds marking off the squares and gardens as discrete elements. The spaces behind them are freely accessible rather than being kept off-limits.

Based on the idea that the existing structures are respected and integrated into the concept, the master plan formulates an initial proposal for the new urban district, which is to be conceived and developed on the basis of its open spaces. In addition to the material legacy of the site, the intangible aspects of its history—the craftsmanship and knowledge that go into the art of shipbuilding— are also taken up so as to remain legible for future generations in the structure of the open spaces and buildings.