Die Gärten des Eiffelturms, Paris

Bauherr

Direction du Patrimoine et de l’Architecture, Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel

Kollaboration

Dietmar Feichtinger Architectes, Paris

Mit nahezu sieben Millionen Besucherinnen und Besuchern pro Jahr zählt der Eiffelturm zu den meistbesuchten Sehenswürdigkeiten der Welt. Die jüngsten Terroranschläge in Paris erforderten es, das Sicherheitskonzept des Ortes zu überdenken, und machten die Einzäunung des Geländes unausweichlich. So ergab sich die Gelegenheit, die Gärten wiederzuentdecken, die früher unter dem Monument existierten. Tatsächlich gab es die Gärten schon Jahre vor dem Bau des Eiffelturms; sie waren Teil des weitläufigen Ensembles des Trocad.ro und des Champ de Mars, das sich von der Colline de Chaillot bis zur École Militaire auf der anderen Seite der Seine erstreckte. Im Laufe der Zeit wurden die Gestaltung und die Komposition des Ensembles jedoch so sehr verändert, dass die Lesbarkeit und Bedeutung der Anlage verloren gingen. Die Reise in die Vergangenheit des Ortes eröffnete die Chance, über die Möglichkeit eines historischen Gartens in der heutigen Zeit nachzudenken sowie über Fragen der Erhaltung, Anpassung und Nachbildung in der Landschaftsarchitektur.

Vom pittoresken décor zum Massentourismus

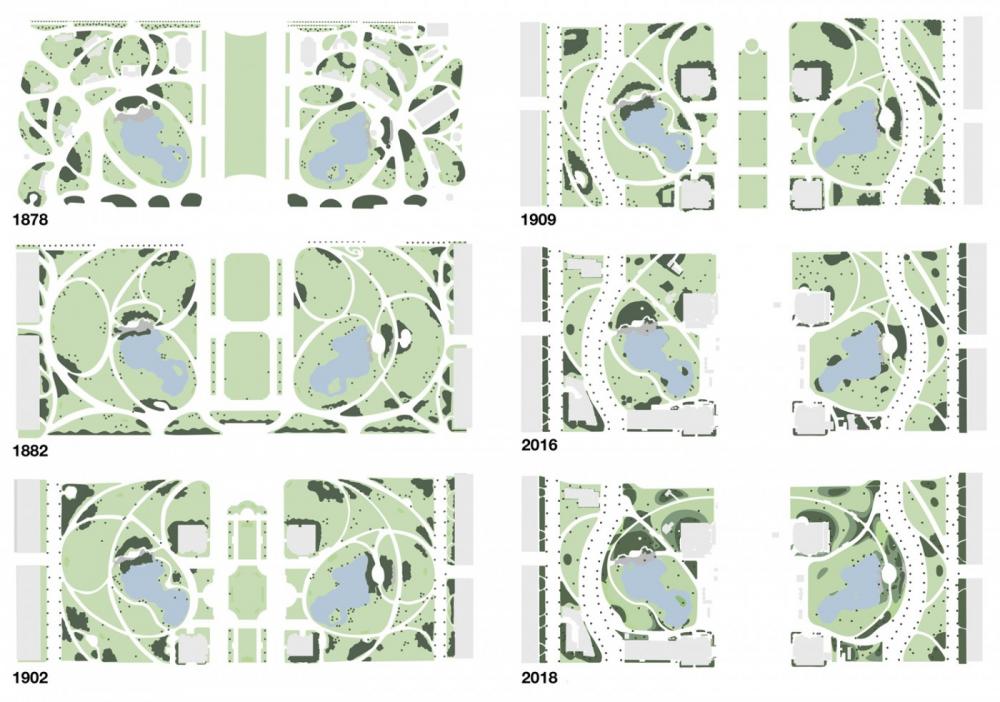

Von Anfang an war das Gelände, auf dem der Eiffelturm steht, diversen Transformationen unterworfen. Nacheinander als maraîchage (Gelände, auf dem Gemüse angebaut wurde) und Exerzierplatz genutzt, wurde der Ort im Zuge der Weltausstellung 1878 in einen Garten umgewandelt, dessen Komposition aus drei robusten Hauptelementen bestand: einer grossen Freifläche mit Fusswegen zum Promenieren, an den Rändern zwei Durchgangswege sowie zwei seitliche Wasserbecken, die am tiefsten Punkt des Geländes angelegt wurden. Durch die Orientierung und Gestaltung der Elemente wurden so unterschiedliche landschaftliche Atmosphären geschaffen. Zwei pittoreske Einbauten komplettierten dieses décor: die Grotte und das Belvedere, beide mit Wasserfällen ausstaffiert. Mehr oder weniger unbeschadet überstanden diese Teile sämtliche Transformationen des Gartens.

Während der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts entwickelte sich der Garten von einer dekorativen Kulisse zu einem Park für die wohlhabenden Bürgerinnen und Bürger der Stadt, während der übrige Teil des Champ de Mars in einen städtischen Park zum Promenieren umgebaut wurde. Die wichtigste Veränderung vollzog sich jedoch im Jahr 1889, als die Gesamtkomposition des Gartens durch den Bau des Eiffelturms zerstört wurde. Das Zusammentreffen des 324 Meter hohen Monuments mit der weitläufigen Fläche des Champ de Mars brachte die spezifische räumliche Komposition hervor, die heute als „die Gärten des Eiffelturms“ bekannt ist und sich nunmehr durch ihre Beziehung zu den riesigen Füssen des Eiffelturms auszeichnete, sich also nicht mehr primär auf das Palais du Trocad.ro ausrichtete. Der eiserne Gigant, auf der ganzen Welt bekannt als Symbol für die Stadt und das Land, ruhte von nun an mit seinen massiven Füssen in dieser miniaturisierten Landschaft.

Mit Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts folgten weitere Transformationen, und eine Reihe von architektonischen Einbauten begann den Rhythmus und die Symmetrien des Gartens weiter zu durchbrechen. Wahllos angeordnete und wild wuchernde Pflanzungen versperrten sukzessive die historischen Blickachsen, über die Jahre hinweg war das ursprüngliche Pflanzkonzept immer weniger lesbar. 2016, als die Stadt Paris ein neues Sicherheitskonzept für den Ort forderte, wirkten die Gärten deformiert und durch den intensiven Gebrauch abgenutzt. Sie wurden praktisch unsichtbar, für die steigende Zahl der Besucherinnen und Besucher gleichermassen wie für die Pariserinnen und Pariser selbst.

Zwischen Erhaltung, Nachbildung und Anpassung

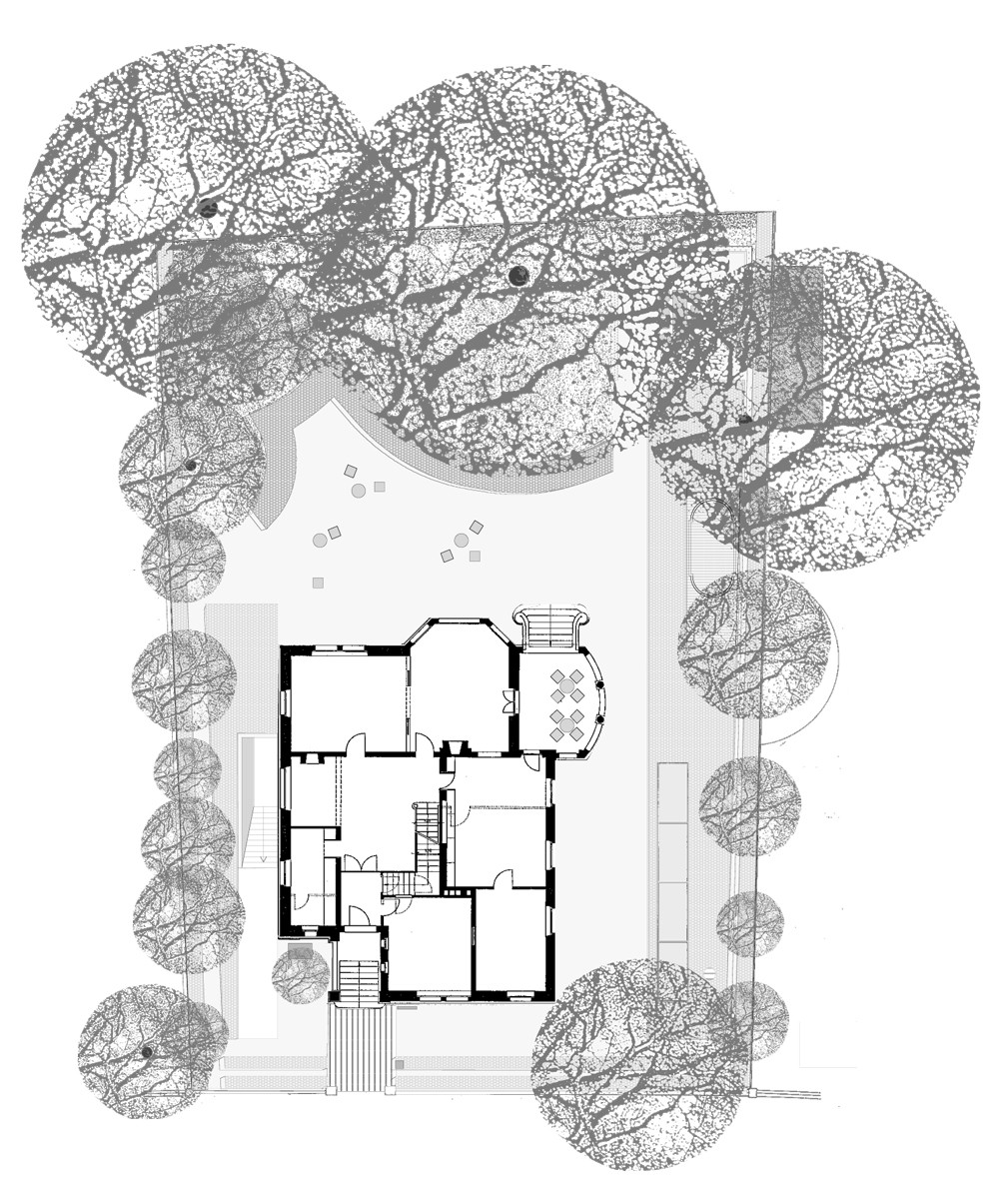

Aus der Notwendigkeit, den Ort aus Sicherheitsgründen einzuzäunen und die Zugänge zu verlegen, ergab sich die Chance, grundsätzlich über den erweiterten Perimeter des Geländes nachzudenken und gleichzeitig die vergessenen Gärten wiederzuentdecken. Trotz aller Veränderungen an den ursprünglichen Gärten waren Spuren der einstigen Komposition der grossartigsten Landschaftsarchitekten und Ingenieure der damaligen Zeit noch immer erkennbar. Mithilfe des schriftlichen Vermächtnisses von Jean-Charles Alphand, Pariser Ingenieur, Stadtplaner und Gartengestalter, wurden einige dieser Elemente und Qualitäten wiederhergestellt. Gleichzeitig legte man neue Wege an, um den Besucherinnen und Besuchern zu ermöglichen, die architektonischen Höhepunkte wiederzuentdecken, die den damaligen Landschaftsarchitekten wichtig waren: die Grotte, das Belvedere, der Schornstein, der Brunnen – das subtile Zusammenspiel der wiederhergestellten und leicht angepassten rocaille, die Pflanzengruppen und die Topografie, die heute so erscheinen, als seien sie schon immer da gewesen. Eine sorgfältig entworfene Choreografie setzt die unterschiedlichen Massstäbe des Projekts miteinander in Beziehung. Der Blick der Besucherinnen und Besucher wandert von den Details dieser Miniaturlandschaft hoch zu dem gigantischen Eisenmonument und durch die transparente Einfriedung des Geländes weiter in die Tiefe der Stadt.

Das Projekt löst die Grenzen zwischen dem Vorhandenen und dem Neuen teilweise auf. Es zielt nicht darauf ab, eine historische Anlage zu bewahren oder einen früheren Zustand des Ortes formal wiederherzustellen. Stattdessen liegt der Schwerpunkt auf der Idee von Kontinuität und Wandel im Garten, fügt der Geschichte des Ortes eine neue Bedeutungsebene hinzu und passt ihn gleichzeitig an die heutigen Erfordernisse und Dringlichkeiten an.