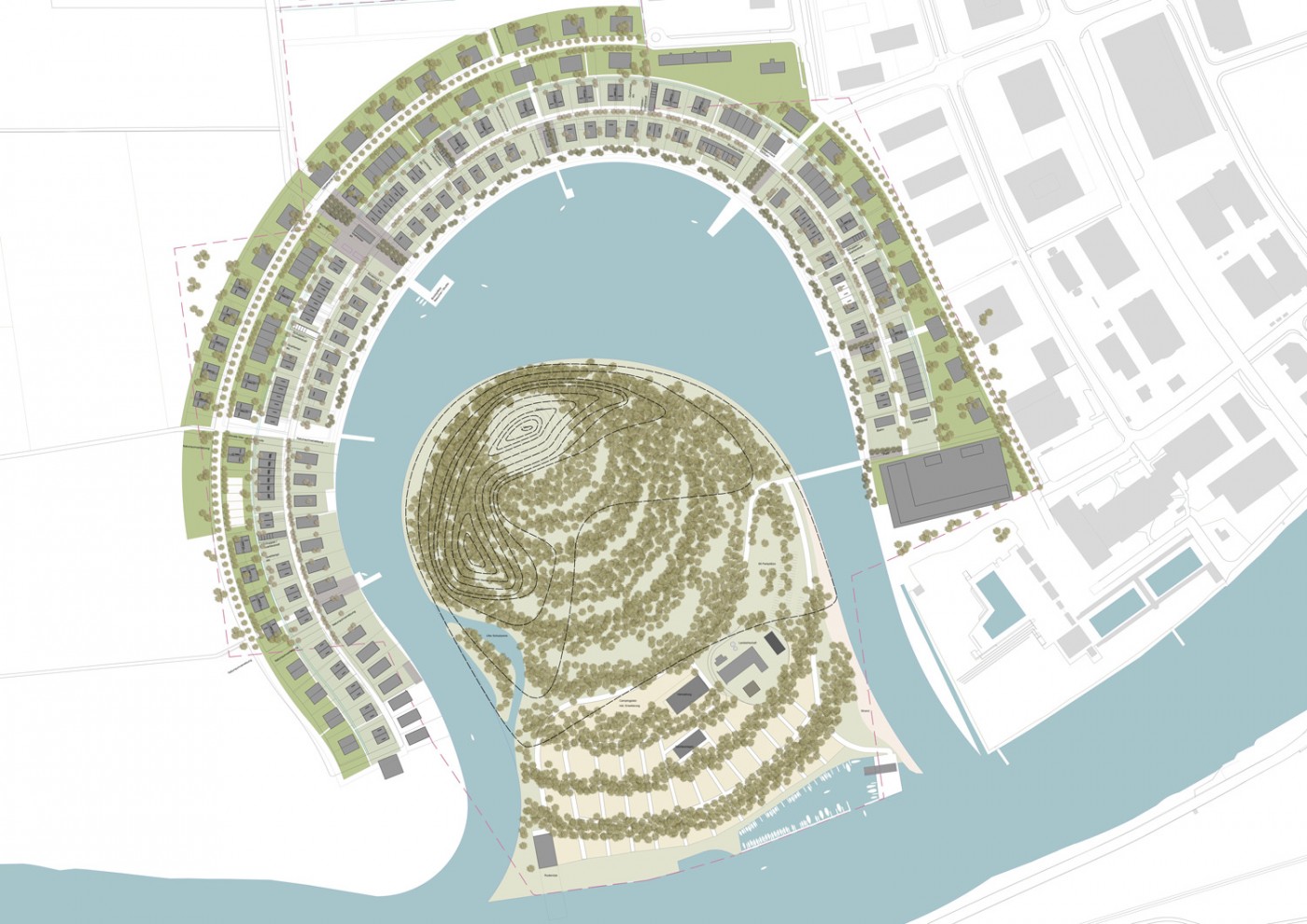

The reclamation of soil and removal of refuse involved in cleaning up Solothurn’s “Stadtmist”—a waste dump that was in operation from 1925 till 1976—is on much the same scale as the processes that formed the landscape of the Aare. The river landscape and its evolution serve as a model for an artificial river loop, on the banks of which the new settlement is to be developed. At the same time, the site is closely intertwined with the surrounding cultural landscape.

The same as the first settlement of Solothurn founded here—a Roman vicus on a green meadow on the banks of the Aare—the Wasserstadt Solothurn or Solothurn Water City project can also be seen as the founding of a new city. As such, it indicates a possible strategy of housing development in the Swiss Midlands. Instead of advocating a random expansion without local specificity, the new estate emerges from the open space and creates specific sites and places directly referring to the landscape and to readable boundaries. The project originally had a different form: structured around district borders and property boundaries, its appearance suggested a marina on the Aare. The qualities and potentials of the site were first brought to light by a detailed study of the landform between the Alps and the Jura. An analysis of scientific maps made it possible to precisely describe the site-specific vegetation, the karst formations created by geomorphological processes, and the hydrological energy of the river. In addition, field trips made it possible to identify, photographically document and cartographically record the old military observation points, which now serve as scenic vantage points for tourists.

The Quarter

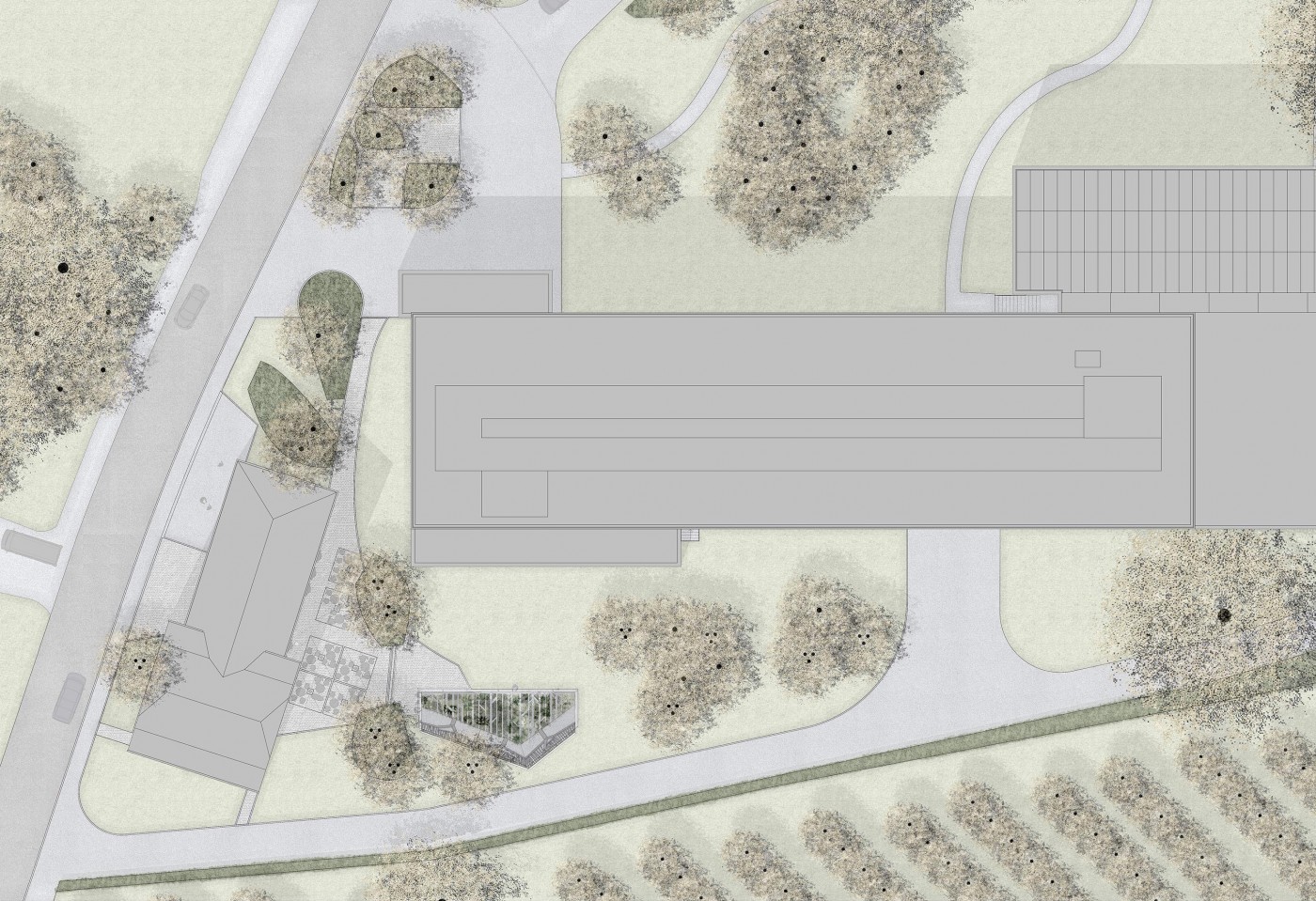

The basic structure of the quarter follows the artificially created river loop, whose pronounced curve traces the earlier course of the originally meandering river. A promenade along the bank with bathing areas and steps leading down to the water form the public backbone of the estate. Running parallel to this are the primary access routes that frame this dense development designed for the highly varied inhabitants of the quarter. Between them is a fine network of squares and greened streets and paths that link the entire neighborhood to the surrounding landscape—the Witi or “expanse” in the local dialect. Hedges line the paths, border the squares, and clearly define the relationship between private and public spaces. The variety of open-space typologies and the diverse uses of the buildings help establish concise urban elements and policies that go beyond any suburban uniformity.

The Island

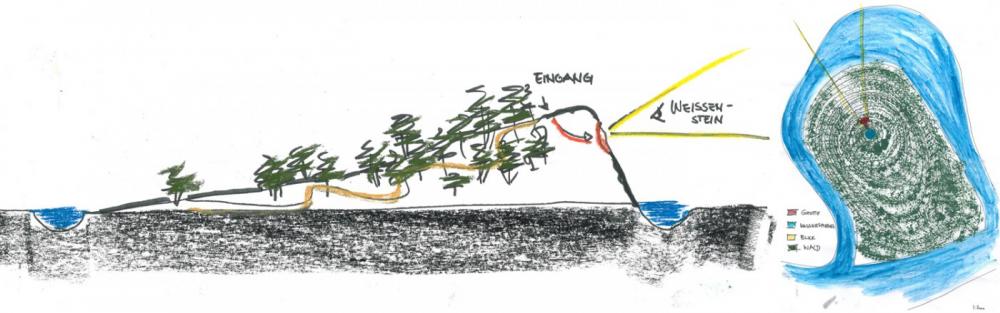

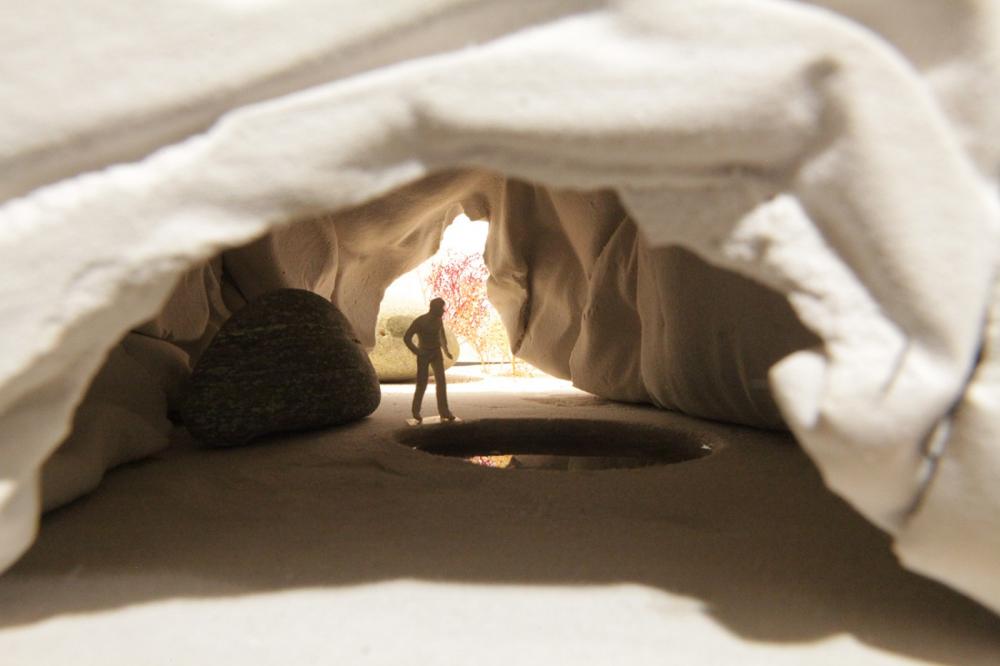

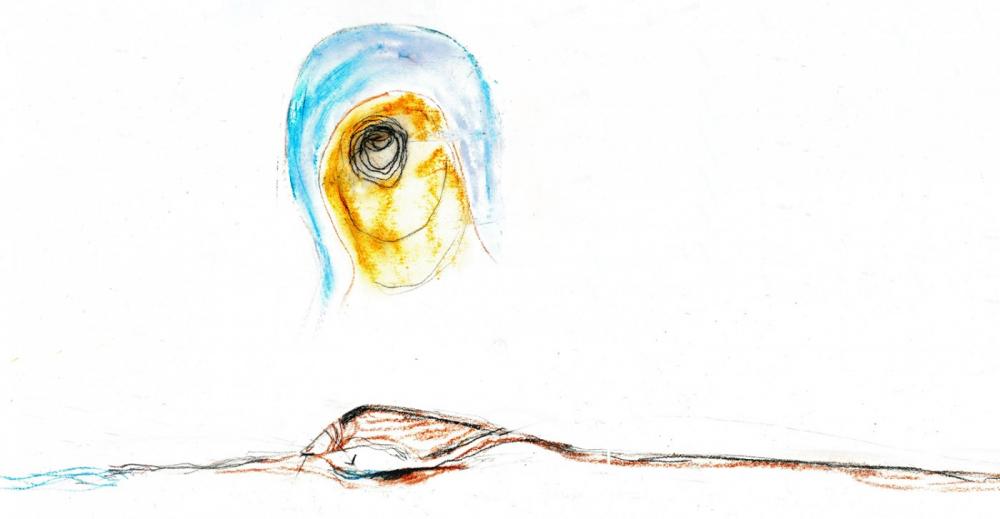

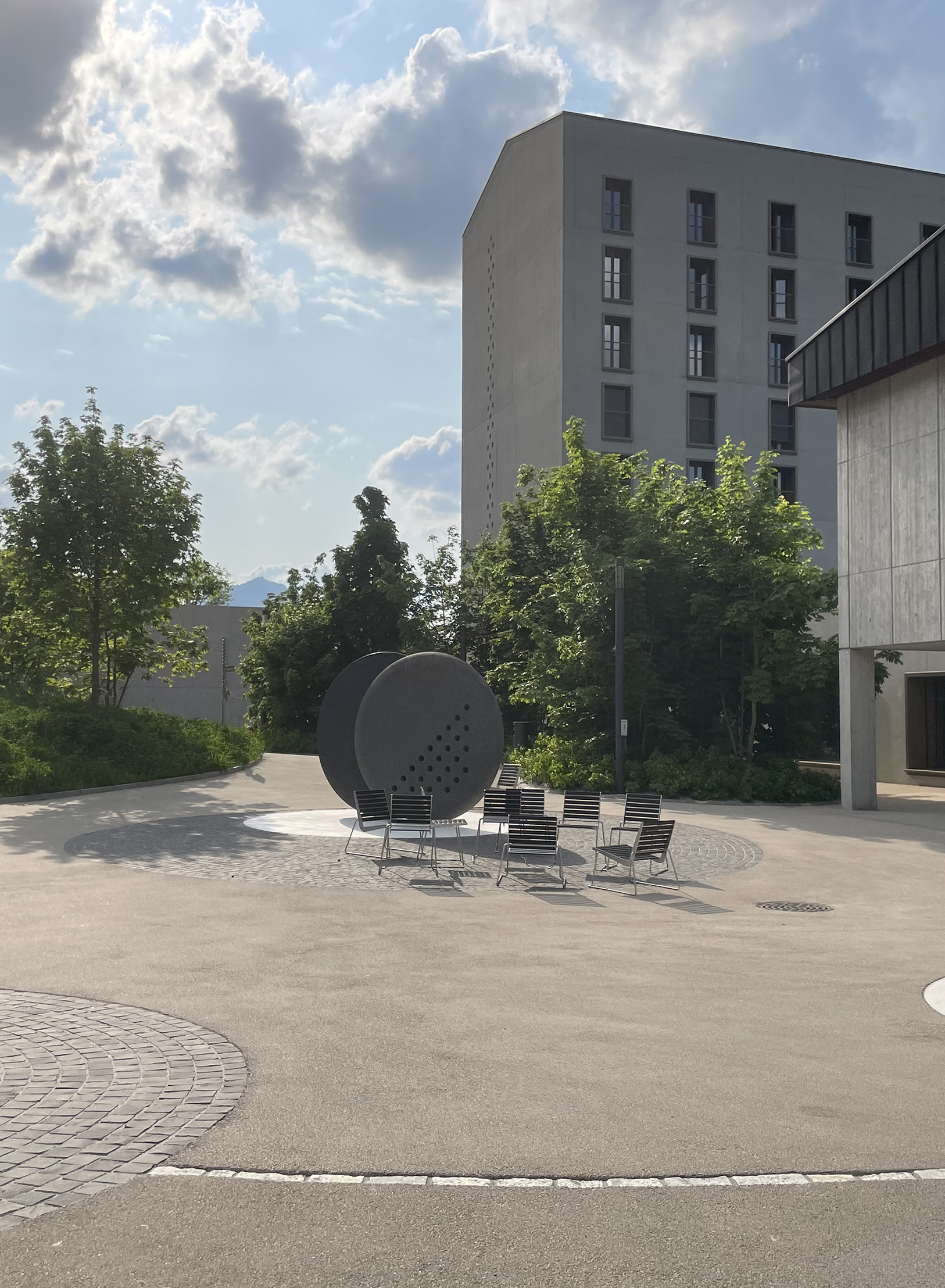

The history of the river loop can best be understood by viewing its formation as having been caused by a “geological obstacle.” The dramatic staging of the island, raised in layers by reintroducing excavated material, accords with the principles of the English landscape park. Coming from the bridge, the only path leads to a lower-lying depression, which is partially flooded when water levels are high, and then proceeds further uphill. The very process of ascending, with the slowly emerging views of the city’s steeples and the landscape features of the surrounding area, thereupon shifts one’s point of view outward. Just before the path reaches the top of the hill, it unexpectedly veers away from the summit and into a grotto that seems to have been eroded from the calcareous rock over millions of years.

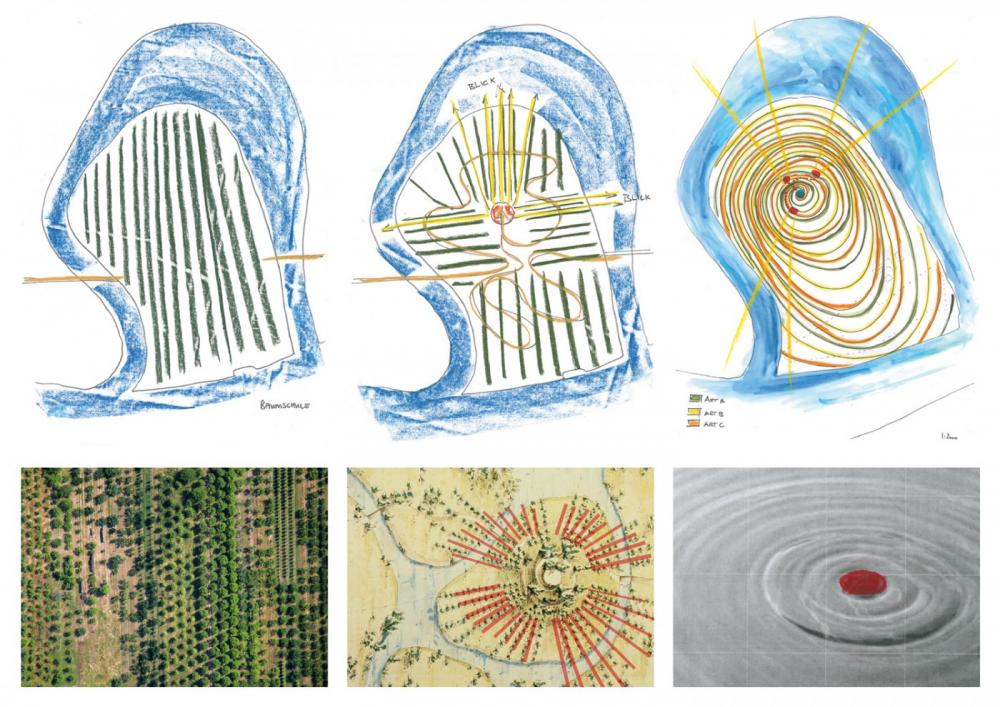

The vegetation is geared to the seminatural surrounding locations. The overall appearance is determined by different species organized according to altitude: whereas the foot of the hill is dominated by small, densely clustered stands of alder, willow, and birch, the ascent is characterized, firstly, by loose groupings of oak and then by mixed woodland consisting of ash and beech. In contrast, the positions of the trees are based on pictures showing the historical park of Drottningholm. However, the organizing principle can only be discerned from higher vantage points. The trees are grouped in concentric ellipses around the high point of the island, creating spaces of varying depth and density reminiscent of an arboretum.

The grotto—which consists of a concrete shell and washed formwork composed of loose gravel— not only illustrates a geomorphological process controlled by anthropogenic sedimentation and erosion but also refers to the local karst rock with its washed-out dolines or sinkholes and miniature glaciers. The grotto also acts as a vantage point directing one’s gaze back to the Jura landscape to which it refers—thus, the erstwhile observation posts become today’s park follies.